Terminology

The terminology used to describe the many conditions that cause painful sex for women can be very confusing.

Dyspareunia: pain with intercourse

Dyspareunia is a general term for painful intercourse and includes pain caused by many underlying causes. This diagnosis doesn’t provide any information about the nature of the pain, but solely acknowledges that it exists. Many conditions that cause vulvar pain in women are similar or overlapping, and many have multiple names. There are names that are officially outdated and shouldn’t be used anymore, but still are. This is part of why it is difficult to locate and understand the published research about these conditions. In 2015, with efforts from leading organizations and doctors, a new classification system was adopted to clarify the language. (2) Vulvar pain was classified into two main categories: pain caused by a specific disorder and vulvodynia.

The first category, pain caused by a specific disorder, covers the more easily identified causes of pain, like infection or trauma/injury. A gynecologist should be able to correctly diagnose this type of condition. Sometimes, these acute problems can lead to chronic pain and become classified as vulvodynia.

Vulvodynia: chronic vulvar pain

Vulvodynia is the category that covers the conditions that I focus on. Vulvodynia is vulvar pain that has been present for at least 3 months with no clear identifiable cause. The suffix “-dynia” means pain and the prefix “vulvo” refers to the location of the vulva. Women with vulvodynia are the ones with chronic pain for no apparent reason, and therefore are more difficult to diagnose. Vulvodynia is characterized by the nature of the symptoms: location (generalized pain the entire vulva or only one structure), provocation (pain is constant or present only when provoked, by touch for example), onset (lifelong or primary, versus developed later in life or secondary), and temporal pattern (e.g. intermittent, persistent). Certain combinations of these characteristics describe individual diagnoses. It is extremely important that doctors collect a full, detailed medical history and do a thorough exam to obtain as much information as possible.

Vulvar Anatomy

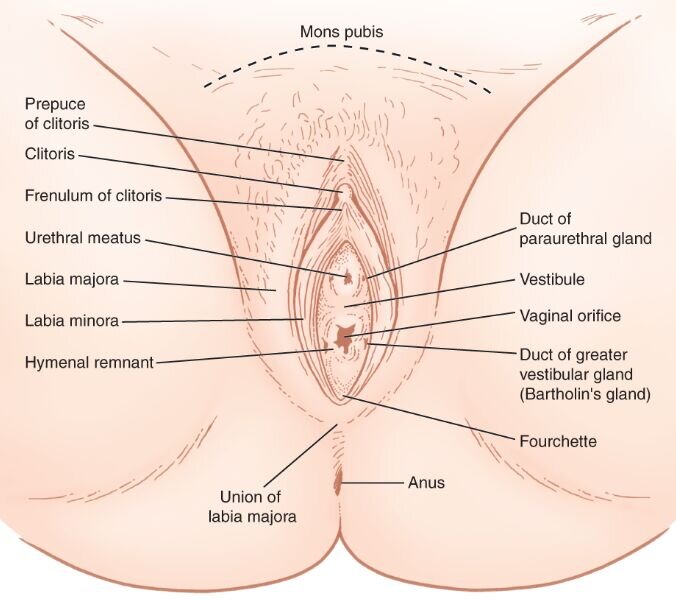

First, let’s go over some more detailed anatomy, because I didn’t even know I had a vestibule until I found out it was the source of all my problems.

Labia majora - the outer folds/lips of the vulva

Labia minora - the inner folds/lips of the vulva

Vestibule - the tissue between the labia minora that surrounds the openings of the urethra and vagina

Urethral meatus - the opening of the urethra, located within the vestibule

Vagina - the muscular canal connecting the uterus and cervix to the outside of the body

Clitoris - the large erectile organ (homolog of the penis); the external part, the glans clitoris, is visible at the top of the labia minora, covered by the clitoral hood/ prepuce

Vulva - all of the outer anatomy: labia, vestibule, vaginal and urethral openings, clitoris

The pelvic floor muscles form a bowl that hold up the internal organs. The urethra, vagina, and rectum pass through these muscles.

If you want more information on anatomy, check out The Pelvic Guru’s Ultimate Anatomy Resource.

Types of Vulvodynia

One of the most common types of vulvodynia is generalized vulvodynia (GD). GD describes a condition with pain throughout the vulva that is unprovoked, meaning there is pain spontaneously. “Women with GD often report constant soreness, burning, or irritating pain throughout the entire vulva.” (3)

The other most common type of vulvodynia is provoked vestibulodynia (PVD). This is what I have. The pain is localized to the vestibule and is only present when provoked, e.g. touch, tight clothing, sitting. Women with PVD usually report pain at the opening of the vagina (where the vestibule is located) when attempting penetration with a tampon or during intercourse. Vestibulodynia can also be unprovoked, characterized by constant pain.

Vulvitis and vulvar vestibulitis syndrome are names that are not typically used anymore, though you may still will see them on the list of diagnoses on a doctor’s form. The suffix “-itis” refers to inflammation. Early research identified inflammation in the painful vulvar tissues, however, we now know that these painful conditions are not necessarily caused by inflammation of the vulvar tissue; therefore, these terms have been replaced with more accurate ones: vulvodynia and vestibulodynia. If inflammation is identified as the cause of the vulvodynia, then these names would be applicable, but that is limited to a subset of patients.

Clitorodynia refers to pain localized to the clitoris. One potential cause is clitoral adhesions, when the hood of the clitoris adheres to the surrounding tissue, which limits movement of the hood and may cause secretions to become trapped. Hyperactivity of certain pelvic floor muscles may also cause clitorodynia. Clitorodynia can also be present chronically or sporadically in a woman with generalized vulvodynia.

The pelvic floor muscles form a bowl of muscle in the pelvis that support the internal organs. These muscles can be too loose or too tight, both of which can lead to pain. Hypertonic pelvic floor refers to muscles that are too tight/short (“hyper-“ means over, so “high tone”). Hypotonic pelvic floor refers to muscles that are too loose/long (“hypo-“ means under, so “low tone”). Pelvic floor physical therapists are trained to help women (and men!) with their pelvic floor muscles. Vaginismus is a condition in which the pelvic floor muscles spasm and tighten when intercourse is attempted, making it very painful and maybe impossible.

It takes a team

Often there are multiple medical conditions to treat in the same woman. For example, most women with generalized vulvodynia or vestibulodynia also have hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction. In these cases, both a sexual medicine specialist and pelvic floor physical therapist would best work as a team to facilitate improvement. Another important team member in many cases is a clinical psychologist, particularly someone experienced in helping people with chronic pain and/or sexual matters. In most cases, vulvodynia has a negative impact on a woman’s sex life, relationships, anxiety, and self-esteem. It is important to also treat the psychological aspects of dealing with sexual pain.

Symptoms, not cause

Because these conditions are classified by symptoms, there are likely multiple root causes of the same condition. Also in 2015, when the new terminology was agreed upon, the current evidence was reviewed on factors contributing to vulvodynia. (2) Research is ongoing, and we need to learn more about all possible contributing factors. As of 2015, the list includes: also having other pain conditions like fibromyalgia or IBS, genetics, hormonal factors, inflammation, muscle issues, nerve issues (both central and peripheral), psychosocial factors, and structural defects. (2)

These many contributing factors likely play a role in certain subsets of patients, either alone or in combination. We have a lot of research to do to, in the future, accurately classify subsets of vulvodynia by cause. Being able to identify the cause of the pain is crucial for proper treatment. Imagine if a broken arm and a skin infection on the arm were both diagnosed as “arm pain,” and doctors tried to treat them both the same way. Obviously, that is not going to be very effective!

This also has major impacts on our ability to carry out research into treatment options. Until we can accurately choose the subset of patients for whom a treatment will most likely be effective, we have limited capability to demonstrate effectiveness. Vestibulodynia is a perfect example. We now know that vestibule pain can be caused by hormonal imbalances OR by too many nerve endings. Clearly, these are different disease processes. Imagine a clinical trial that is testing the effectiveness of topical hormone treatment on the vestibule in women with vestibulodynia. Some of the women in the study will have vestibulodynia caused by hormone imbalance and others will have vestibulodynia caused by too many nerve endings. The hormone treatment will work for some women (the ones with hormone imbalance), but the overall results of the study will be poor because the treatment will not work for many patients, and it will not be recommended as a good treatment for vestibulodynia. Now that the two separate causes of vestibulodynia have been recognized, this exact study was done in a more appropriate patient population, only women with vestibulodynia who are also taking hormonal birth control, and the results show that stopping the birth control and using topical hormones is very effective. (4)

Sexual medicine specialists that participate in research studies are doing their best to advance our knowledge about vulvodynia so that the best treatments can be identified. For now, we are still in the early stages and I’ll share important new findings as they are published. The more we can learn about the details of the biology of these conditions, the better the treatments will become.

References

1. Main source: Irwin Goldstein, Anita H. Clayton, Andrew T. Goldstein, Noel N. Kim, and Sheryl A. Kingsberg. 2018. Textbook of Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction, Diagnosis and Treatment. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Hoboken, NJ. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781119266136

2. Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, Bergeron S, Pukall C, Zolnoun D, and D Coady. 2016. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. Journal of Sexual Medicine 13(4): 607-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27045260

3. Amy L. Stenson. 2017. Vulvodynia: Diagnosis and Management. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 44(3): 493-508. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28778645

4. LJ Burrows and AT Goldstein. 2013. The Treatment of Vestibulodynia with Topical Estradiol and Testosterone. Sexual Medicine 1(1) 30-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25356284 Open Access Journal Direct Link: https://www.smoa.jsexmed.org/article/S2050-1161(15)30010-6/fulltext